British and American writers and artists in 1920s Tahiti

March 21, 2025

I am currently writing a book on the British and American ex-pats who moved to Tahiti in the 1920s. Below is the introduction:

The British author, Robert Keable arrived in Tahiti at the end of 1922. He was on an extended honeymoon with his common-law wife Jolie Buck, having just separated from his newly converted catholic wife Sybil. It was claimed in one press briefing that he was looking for peace and quiet so he could complete his sequel to his first novel Simon Called Peter. By April 1923 he had sent Recompense off to his publisher. So, he decided to write a book on Tahiti.

He certainly didn’t need to write the book. He didn’t need the money. The success of his first three novels, published in the space of 18 months had earnt him – in 1922 – at least ten times his annual teacher salary.

And he was fully aware that there wasn’t obviously a need for another book about Tahiti. He wrote:

Of the making of books upon the South Seas there is no end, and there probably will be no end for a long time… of books about Tahiti in especial there might be thought to be enough… It has been written up from the geographical, the historical, the missionary and the romantic standpoint – especially the romantic[i]

However, he goes on to suggest that there may be a gap in the market for a book looking at the dreams which attracted the great artists and writers like Loti, Gauguin, Robert Louis Stephenson and Rupert Brooke to come to the island and the reasons why they did not stay.

His intention from the start was to show that the island had been ruined by western civilisation. He argues throughout the book that visitors to the island were attracted by an unrealistic dream. And he explained the reality.

The old Tahiti is as dead as the Middle Ages. Its people have been exterminated, its beauty has been ravished, and its very tradition almost obliterated. The tourist of a day or even of a month sees no more of the real Tahiti of the past than he would see at a well conducted Colonial Exhibition. If he wants amorous adventure he had much better go to Paris. If he wants primitive simplicity he had better go … to Central Africa. And if he wants to get every material necessity for nothing he had better shoot himself [and go to] the Astral Plane.[ii]

If that wasn’t damning enough, he went on to explain:

The average young tourist who comes to Tahiti runs an even greater chance of contracting venereal disease then anywhere else in the world. The average lunatic in search of a simple life usually leaves in six months to rid himself of elephantiasis or something worse. The individual who, with the best will in the world, seeks in Tahiti an easy life, almost certainly departs broken-hearted in less.[iii]

Not surprisingly Keable’s American publisher decided not to publish the book explaining to Keable’s agent ‘the book would not have sufficient appeal for the American public to warrant Putnams publishing it.’ Keable must have expected this. He explained earlier in the book:

A friend of mine, a young and struggling author, recently sent home articles and photographs of Tahiti. His agent submitted his stuff to the magazines, and wrote to him of the result. In effect he said: ‘They say you write well and can easily market your goods. But if you photograph, your pictures must show no sign of a telegraph pole or a motor-car, and if you write you must not abuse that conception of a real South Sea island which recent writers have done so much to inscribe on the public mind and which the public wants.’[iv]

One might expect, after all his negative comments, that Robert Keable would have copied his literature heroes, like Robert Louis Stevenson and Rupert Brooke, and after a short stay would have left the island forever. But he continued to live on the island, building his own house and eventually marrying a Tahitian princess Ina Salmon. And he was not the only one to move to Tahiti.

William Alister Macdonald, born in Scotland, but living in London was 60 when he left his wife Lucy and their 11-year-old son and moved to Tahiti. Like Keable he had achieved success, as a well-respected water colourist, part-time teacher and sometime art dealer. Like Keable he ran away with a younger woman, (Dorothy was 31, Jolie 23), who at the first opportunity took his surname. And like Keable he settled in Tahiti and when his new partner departed – (Dorothy went home after three years, Jolie died in childbirth after two), he lived with a Tahitian woman and had a child together.

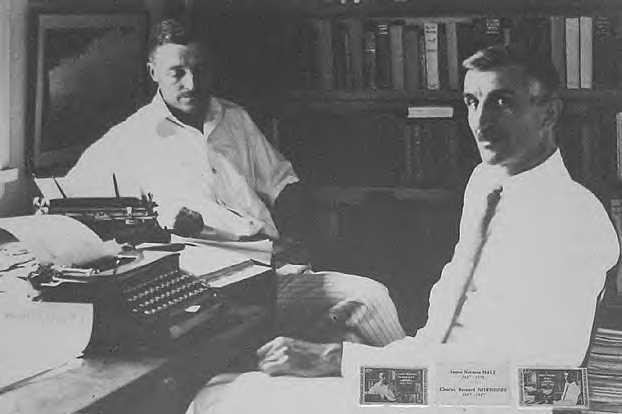

Keable and Macdonald did not know each other before they ran away and there is no actual evidence they knew each other in Tahiti, although it seems inconceivable that they did not meet. They did however both meet and become good friends with two Americans who moved to Tahiti in 1920. Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall did not exactly run away to Tahiti. They were sent to the island by Harper’s Magazine to write articles which were later collected together in the book - Faery Lands of the South Seas. But they both stayed on, Nordhoff for twenty years and Hall for life. Both were the same age as Robert Keable. Both married local women whose Tahitian mothers had European partners. Christianne’s father was Danish, Sarah’s English.

So why did these four men decide to settle in Tahiti? There are thousands of islands in the South Pacific and more than 130 sizable islands (over 100 square kilometres). Tahiti is the 44th biggest. Why go there? And there were others too who moved to Tahiti and the nearby islands in the 1920s. Robert Dean Frisbie; Jack Hastings, the Earl of Huntingdon; RJ Fletcher; Eastham Guild; Harrison Smith and more. And some who came for extended visits like George Biddle and Alec Waugh.

My interest in Tahiti came initially from exploring the life of my grandfather, Robert Keable. It took me a while to realise that Keable’s experience in Tahiti was not unique. What, I wondered, was the attraction of Tahiti which bought these men to the island? What were their stories? What were they running away from? And what kept them there?

Writing as I am in the 2020s it seems an apt time to ask these questions. The coronavirus lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 have changed people’s, and business’s, outlook on work. Going into the office is no longer seen as essential for many workers and there has been a big increase in the number of people moving abroad and taking their work with them. It has been estimated that there are over 35 million people digital nomads[v] – a term popularised by Tsugio Makimoto and David Manners in 1997.[vi] Not that many have gone to Tahiti. The most popular island destinations are Bali, Madeira, Barbados, Cozumel (Mexico), Phuket and Koh Phangan (Thailand), Gran Canaria, Malta and Curaçao.[vii] Tahiti does not make the list presumably because it is so expensive. Sylvain and Mélanie [viii] estimate on their website that anyone planning to live on Tahiti would have to pay at least £10,000 in the first month just to begin to get settled with a house to live in and the essential car to get around. Once settled things are expensive, especially electricity, and food is 40% more costly than in France. To live comfortably a couple would need to spend more than £30,000 a year, three times the cost of living on, as an example, Bali.[ix]

Here there is a definite similarity with the 1920s. Back then it was very expensive to travel to Tahiti and also costly to live there in any sort of comfort. And as today it was mainly the French who settled on the island often in the employment of the government. Unsurprisingly the British and American visitors to the island in the 1920s who settled were either wealthy or were earning enough from their work as writers or artists to carry on living on the island. They were perhaps the first digital nomads, with typewriters or paint and canvas for laptops. But for many the desire was to escape from the rest of the world, not to stay connected.

[i] Robert Keable, Tahiti, Isles of Dreams, Hutchinson & Co., 1925, Preface

[ii] Robert Keable, Tahiti, Isles of Dreams, pp208-209

[iii] Robert Keable, Tahiti, Isles of Dreams, p.209

[iv] Robert Keable, Tahiti, Isles of Dreams, p.24

[v] https://www.localyze.com/blog/digital-nomad-statistics-trends-2023-2024

[vi] Tsugio Makimoto, David Manners, Digital Nomads, Wiley 1997

[vii] David Brown, Digital Nomad Hotspots, https://www.islaguru.com/articles/top-island-for-digital-nomads#, Sep 9th 2024

[viii] Sylvain & Mélanie, Going to live in Tahiti, https://lesdeuxpiedsdehors.com/en/live-in-tahiti-french-polynesia/

[ix] Cost of living in Bali, https://internationalliving.com/countries/indonesia/cost-of-living-in-bali/